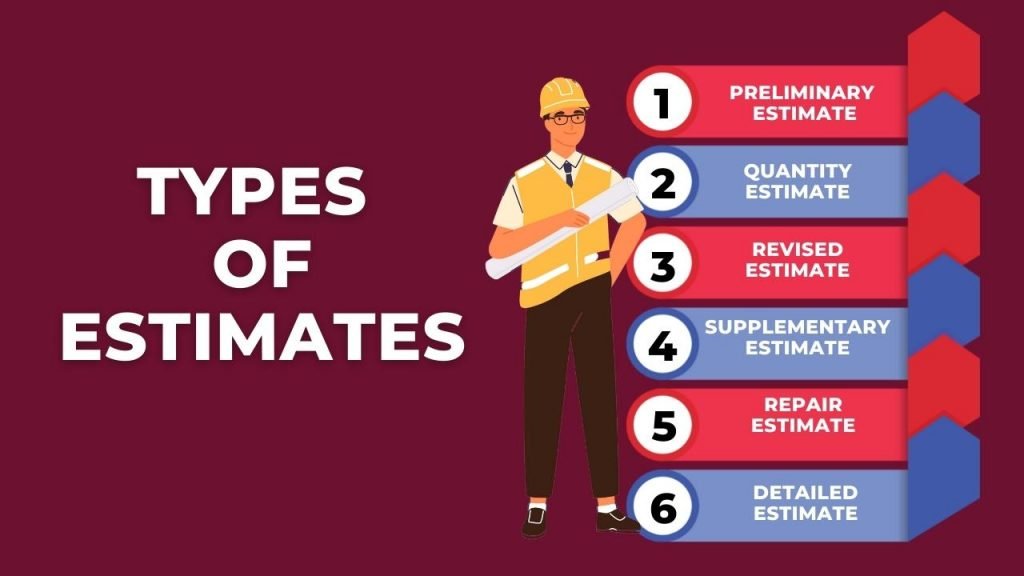

An approximate estimate (also called a preliminary or rough estimate) is a quick, high-level forecast of a construction project’s cost. It’s prepared early on, often with only basic information or sketches. The goal is to get a ballpark figure fast to aid decision-making. As one source explains, this “approximate estimate is prepared for preliminary studies of the work’s various aspects and to decide the financial position and policy for administrative approval by a competent sanctioning authority”. In simple terms, it’s a starter estimate – enough detail to see if a project is feasible, but not a full detailed budget.

Approximate estimates are based on past experience and broad measurements. Typically engineers use data from similar completed projects or standard rates (from government Schedules of Rates) and simple formulas. For example, they might multiply a building’s area by a typical rate per square foot (SRC-constructionplacements). The estimate will list major cost items – land, buildings, roads, water supply, etc – with rough costs for each. This approach uses practical knowledge of similar works, as noted by industry guides. Because it relies on known rates and rules of thumb rather than detailed blueprints, an approximate estimate can be done very quickly.

In practice, an approximate estimate might include a simple site layout or sketch instead of full drawings. No detailed surveys or take-offs are needed – just enough information to measure area or volume. In many cases only a line sketch of the project is prepared(SRC-theconstructor). This makes the process fast and inexpensive. According to one construction resource, “preliminary investigation and preliminary surveying are enough to prepare [an approximate estimate]” and “records for similar works or practical knowledge helps in determining the rates”. In short, approximate estimates use broad inputs (like built-up area or length of road) and standard rates from past jobs, instead of detailed material quantities.

Why Are Approximate Estimates Used?

Approximate estimates play a critical role in early project planning. They help stakeholders quickly gauge feasibility and decide whether to invest more time. As one guide notes, approximate estimates give a “basic or starting point estimate for any project” and help decision-makers decide whether to proceed. If the rough cost looks too high, a project can be shelved early, saving effort. Conversely, if the estimate is reasonable, the team will move to detailed planning. In fact, the estimate “helps the takers of the project to make a decision as to take up the project or not”.

Government authorities or investors often require a preliminary cost estimate before sanctioning funds. For example, an approving body may ask for an approximate budget to review the financial aspect of a project. This estimate “enables the concerned authority to consider the financial aspect of the scheme to accord sanction”. In practice, preparing an approximate estimate is a standard step for budget approval and feasibility checks.

Once an approximate estimate is done, it serves as the basis for more detailed planning. A common warning is that if the final detailed estimate far exceeds the approximate one, the project may need to be cancelled to avoid waste. One source explains: if the “approximate estimate is too high, then the project manager would leave the project without preparing the detailed estimate… if [the] detailed estimate is much higher than the approximate estimate then the project may be cancelled”. In short, approximate estimates save time and resources by catching potential cost overruns early.

Approximate estimates are also used to check budget feasibility. They give a quick idea of the funds required. As one guide states, an approximate estimate “gives an idea of the probable expenditure in a short time. This idea of expenditure ascertains the practicability or feasibility to take up the project based on the availability of funds”. In other words, before spending time on detailed drawings, the project owners can see if they can afford the work.

Table 1: Key Features of Approximate (Preliminary) vs Detailed Estimate

Feature Approximate Estimate Detailed Estimate When Concept/feasibility stage After plans are finalized Data used Sketches or basic dimensions Full drawings, specifications How calculated Broad formulas (area×rate, volume×rate) Item-by-item takeoff of quantities Accuracy Low (roughly ±20–30%) High (often within 5–10%) Time & cost Quick and cheap to prepare Time-consuming, more expensive Purpose Feasibility, admin approval, budget check Final tender, contracts, billing

This comparison highlights that approximate estimates trade accuracy for speed. They use simple rules (see Table above) and may be off by about 20–30%. But in exchange, they let stakeholders make early decisions without waiting for full designs.

Common Methods of Approximate Estimation

Several simple methods exist for approximate estimates, each suited to different situations. The most widely used methods include:

| Method | How It Works |

|---|---|

| Plinth Area Method | Estimate cost = Plinth area × Plinth area rate (₹ per sq.m). Plinth area is the building’s covered floor area (external dimensions). The rate is chosen based on similar buildings in the region (from CPWD or local data). For example, a building with plinth area 2,500 m² at ₹25,000/m² costs ~₹62.5M. |

| Cubic Content Method | Used for multi-storey buildings. Cost ≈ Total volume × Local cubic rate. The volume (length×breadth×height) is multiplied by a rate per cubic meter. This accounts for height, unlike plinth area method. |

| Unit Base Method | Choose a “unit” relevant to the project (e.g. per bed in a hospital or per student in a school). Estimate = Total number of units × Cost per unit. The unit cost is derived from past projects (actual cost of similar building ÷ number of units). |

| Approximate Quantity Method | Divide the structure into two parts: foundation (including plinth) and superstructure. For each part, calculate the total length of walls in running meters. Then multiply foundation length by a foundation rate, and wall length by a wall rate. Sum these for total cost. |

Each method is only a rough guide. For example, the plinth area method ignores differences in wall thickness or finishes, and the cubic method ignores things like non-enclosed spaces. Therefore, experienced estimators use these methods with judgement and often allow for a margin of error.

How to Prepare an Approximate Estimate

To prepare an approximate estimate, follow these general steps:

- Gather Project Details. Get a basic sketch or layout of the project (site plan, building plan, etc.). You may only need a simple line drawing at this stage. Determine key dimensions such as building footprints, total floor area, or expected volume.

- Select the Method. Choose the most suitable estimation method based on project type. For a regular building, the plinth area method is common; for complex multi-story or irregular projects, cubic content or unit methods may be better.

- Determine Standard Rates. Obtain standard rates from reliable sources. In India, common sources include the CPWD Schedule of Rates (SoR) or recent government project data. For example, CPWD publishes plinth area rates (₹/m²) for different building types, or one can use rates from similar recent projects. The selected rate should match the building quality, location, and type.

- Calculate Component Costs. Apply the chosen method. For instance, if using plinth area method, multiply the building’s plinth area by the plinth rate (₹/m²). If using volume, compute length×width×height and multiply by the cubic rate. For unit base, multiply total units by unit cost. If using approximate quantity, calculate lengths of walls for foundation and superstructure and multiply by respective rates.

- Add Contingency. Because this is a rough estimate, include a contingency allowance for uncertainties. Industry practice is to add about 5–10% of the total for contingencies. This covers unforeseen costs like slight design changes or price fluctuations.

- Prepare a Brief Report. Document how you derived the estimate. Even at this stage, it’s good to include: the project’s purpose and scope, data sources, the method used, rates applied, and assumptions made. TheConstructor suggests including items like the origin of the proposal, necessity, the basis of estimate, and cost breakdown. Also attach the layout plan or sketch. This report helps decision-makers understand the estimate. Example: If you are estimating a small house, you might take the plinth area (say 100 m²), multiply by a local rate (say ₹2,500/m²), giving ₹250,000. Then add 10% contingency (₹25,000) for a total of ₹275,000 as the approximate estimate. This quick figure tells you the project likely costs around ₹2.75 lakh, sufficient to decide whether to proceed with detailed planning.

By following these steps, you get a rough budget without detailed take-offs. The process leverages rules of thumb and past data, making it fast. It’s much easier than a full item-wise estimate, but remember its accuracy is limited.

Also Read What are Pavements & Their Types? – A Complete Guide for Civil Engineering

Importance in Project Planning

Approximate estimates are crucial for project planning, budgeting, and approvals. Some key points:

- Administrative Approval: Many public projects require a sanctioned estimate before work can begin. The approximate estimate fulfills this requirement by showing preliminary cost projections. Government bodies (e.g. local municipal corporations) often request a rough estimate to release initial funds or permits.

- Budget Allocation: Owners and financiers use the estimate to allocate a budget. It sets an expected cost ceiling. Without it, projects may be under- or over-budget from the start. A quick estimate “helps the relevant authorities examine the financial component of the project”.

- Feasibility Study: Developers check if projected revenues justify investment. For revenue projects (commercial buildings, irrigation schemes, etc.), approximate estimates include potential income projections to see if the project is justified. For non-revenue projects, they assess utility versus cost.

- Early Decision-Making: Management can compare multiple project options. For example, if a city has to choose between building a new road or a bridge, an approximate estimate of each can guide which is more feasible within the available budget.

- Risk Management: By revealing likely costs early, approximate estimates help mitigate risk. If initial numbers look too high, plans can be revised or canceled before wasting resources on full designs. One guide notes that if the detailed estimate ends up far above the approximate one, “the project may be cancelled,” preventing larger losses.

For Indian construction projects, approximate estimates often align with local practices. For instance, engineers in India typically follow CPWD (Central PWD) guidelines or state PWD schedules.They use published plinth area rates from these schedules (given in INR) to calculate building costs. That means an estimate will often be in lakhs or crores of rupees. (For example, one case calculated 2,500 m² at ₹25,000/m² ≈ ₹6.25 crore.)

Accuracy and Limitations

By design, approximate estimates are imprecise. They may vary by ±20–30% or more from actual costs. This is acceptable for early stages. Accuracy depends on how good the underlying data is: a very rough sketch and outdated rates give a cruder result. As a rule of thumb, one source lists the accuracy of preliminary estimates as around ±30%.

Because the input data is limited, exact features are ignored. For example, special architectural details, floor height differences, or complex MEP (mechanical, electrical, plumbing) works aren’t captured in most approximate methods. Therefore, one must treat the outcome as indicative, not final.

Contingency: To partly offset this uncertainty, we add a contingency (about 5–10%). This cushion helps account for missing details. Even then, stakeholders understand that the final cost (after detailed design) could be higher or lower than the approximate estimate.

Importantly, an approximate estimate is not a substitute for a detailed estimate. It’s a planning tool only. Once a project passes the initial screen, a full quantity estimate should be prepared before construction. Only a detailed, item-by-item estimate can provide the precision needed for contracts, bidding, and construction planning.

Conclusion

In summary, an approximate estimate in construction is an early-stage cost projection made with minimal data. It is quick and easy, relying on standard formulas and past project rates, and is used to assess the viability of a project before detailed design work begins. While not highly accurate, it provides a rough budgetary figure that helps clients and authorities decide whether to move forward. By comparing this initial estimate against available funds or expected revenue, stakeholders can make informed go/no-go decisions.

In India, approximate estimates often follow government norms (e.g. CPWD plinth area rates) and are crucial for obtaining administrative approval. However, one must remember its limits: it is a guide, not a guarantee. Once an approximate estimate shows a project is viable, the next step should always be a full detailed estimate for execution.

Key Takeaway: Use approximate estimates early to get a rough project cost fast, include a small contingency, and always back them up later with detailed costing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What exactly is an approximate estimate?

A: It’s a rough, preliminary cost estimate made early in a construction project. It uses basic project dimensions and standard rates to give a ballpark figure. It’s sometimes called a preliminary or budget estimate.

Q: When should I use an approximate estimate?

A: Use it in the concept or feasibility phase – before detailed designs are complete. It’s ideal for initial budgeting, getting project approval, or comparing different project options.

Q: How accurate are approximate estimates?

A: They are not very precise, often only within ±20–30% of actual costs. Their accuracy depends on how well you know similar past costs and choose appropriate rates. Always treat them as a rough guide.

Q: What methods are used for approximate estimates?

A: Common methods include: Plinth Area Method, Cubic Content Method, Unit Base Method, and Approximate Quantity Method. Each uses a simple calculation (area×rate, volume×rate, etc.) as shown in the table above.

Q: Do I need full drawings for an approximate estimate?

A: No. A detailed drawing is not needed. A simple plan or sketch is usually sufficient. You just need enough to measure areas or volumes roughly.

Q: How do I choose rates for the estimate?

A: Rates can come from past similar projects or published schedules. For example, in India, you might use the CPWD Schedule of Rates for concrete, labor, or per sq.m. building costs. Use rates that match your project’s specs.

Q: Should I add contingency to my approximate estimate?

A: Yes. It’s recommended to add about 5–10% for contingencies. This covers unknowns since your data is not detailed.

Q: Can an approximate estimate be used for project bidding or contracts?

A: No. It is only for preliminary planning. For bidding or final budgeting, you must do a detailed estimate based on full quantities and specifications

Q: What information should accompany an approximate estimate?

A: Usually a short report is attached, listing the project’s scope and explaining how costs were derived. Items include sources of data, necessity of work, cost basis, and funding methods.

Q: Why might a project be canceled after an approximate estimate?

A: If the rough cost is far above available funds or expected return, stakeholders might drop the project early to avoid wasted effort. Approximate estimates help prevent overspending by flagging expensive projects upfront.